Grief is a universal experience that impacts people of all ages, backgrounds, and walks of life. Grief can be a tremendously painful and difficult process to traverse, whether it is the loss of a loved one, a pet, a job, or even a way of life. It can leave people feeling confused overwhelmed, and alone, with no idea how to proceed. The diversity of grief models reflects the grieving process’s complexity and individuality. Grief is a very individualized experience shaped by a variety of elements, including culture, personal values, and the nature of the loss.

Each model of grieving provides a distinct viewpoint, assisting individuals and professionals alike in comprehending, articulating, and navigating the complex emotions connected with loss. Different models offer different frameworks for comprehending grief’s stages, allowing for a more nuanced examination of the various ways people cope and adapt. While some people may identify more with one model than another, the wide range of grieving models recognizes that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to the grieving process.

Also read: How to handle Grief?

By integrating personal life experiences into the model, counsellors can develop a deeper understanding of the unique challenges and needs of their clients, leading to more tailored interventions and enhanced empathy. This blog will delve into the background of the Kubler Ross Model, highlight the importance of incorporating personal life into the model, discuss the six stages of grief, examine how personal life experiences relate to each stage, and explore the benefits of integrating personal life into the model.

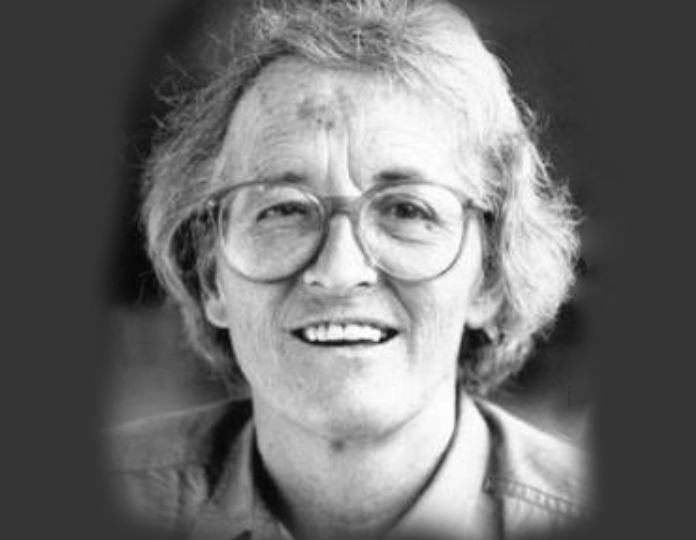

Kubler Ross Model

The Kubler-Ross Model of Grief, also known as the Five Stages of Grief, was developed by Swiss-American psychiatrist Elisabeth Kubler-Ross. In her seminal work, “On Death and Dying,” Kubler-Ross outlined the stages that terminally ill patients often go through when facing their own mortality. The model originally consisted of five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Over time, a sixth stage, finding meaning, was added to the model. This model revolutionized the understanding and treatment of grief, providing a framework for individuals to navigate the emotional and psychological challenges associated with loss. Understanding the background of the Kubler-RossKubler Ross Model Model is essential for comprehending its relevance and the potential benefits of incorporating personal life into the model.

As a trainee therapist, I have experienced the profound effects of loss on both a personal and professional level. The Kubler-Ross 6-stage model, a compass in this emotional terrain, has been important in understanding not only the experiences of clients I see, but also my own encounters with loss. As I progressed through the stages—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance, and finally, meaning-making—I discovered a profound guidance that mirrored the complexity of grief.

Surprisingly, when applying the model to client losses, the identification stages appeared fairly natural. However, as I turned the lens inward to navigate my own grief or the grief of a loved one, a unique challenge unfolded. It’s as if the model’s familiarity made the procedure easier for others to understand, but applying it to my personal experience added a thoughtful depth of introspection.

Personal Reflection and Client Connections

In one case, a client who was grieving the loss of a beloved pet found solace in identifying with the bargaining stage. This awareness enabled them to acknowledge the innate human need to undo the irreversible, even in the face of the loss of a valued relationship. On a personal level, when I applied the model to my own experience, especially the death of my grandmother, the stages of grieving revealed a complicated interplay of feelings and thoughts. Recalling examples from my sessions, I saw how the model created a conversational bridge, allowing clients to express and comprehend their grief in a common language. It was in these moments when the universality of grief manifested itself, surpassing the bounds of professional responsibility and personal empathy.

Kubler-Ross’s Non-linear Concept:

Kubler-Ross’s concept describes grief as a complicated, non-linear process. It inhibits a simple sequence of events, reflecting the complex internal workings of a human being. This model takes into account the complex and varied facets of the human experience, acknowledging that grieving is not a straightforward or effortlessly comprehended event. Within the framework of Kubler-Ross’s concept, grieving is like trying to find your way through an unfamiliar emotional maze. Visualize it as a labyrinth, with each turn standing for a distinct grieving stage, such as acceptance, bargaining, denial, rage, and sadness. The journey is unpredictable, much like traversing through twists and turns, encountering moments of confusion, and occasionally finding oneself at a crossroads.

Also Read: Coping with Grief and Loss: A Guide for Young Adults

There are moments when the route comes to an emotional dead end, reflecting the difficulties and disappointments encountered during the grieving process. Nevertheless, every stride offers a chance for development and introspection, leading to the labyrinth’s centre, where healing and acceptance are waiting for you. This metaphor tries to effectively conveys the intricacy, unpredictability, and transforming capacity inherent in the grief process.

The Protective Veil in the Face of Loss

The denial stage is generally the first emotional reaction to loss, marked by a refusal to accept the terrible reality. People who are going through the denial stage of sorrow could be compared to an ostrich that has its head buried in the sand during a storm. The ostrich’s protective instinct is a protection mechanism against the overwhelming storm, not a sign of ignorance. Similarly, denial provides a temporary buffer from the emotional storm after the first shock of loss. The denial stage gives you a little reprieve and a chance to regain strength before moving on to the other phases of mourning. In the midst of grief, denial sets off a complicated chain reaction of biological and physiological reactions.

Stress is triggered by the autonomic nervous system, which controls involuntary body processes. The body fights admitting the painful reality of the loss since it is in a protection mode. Behaviourally speaking, people may engage in strategies of avoidance at this point, avoiding conversations or circumstances that compel them to face the matter as it is.

When I thought back on my own experiences, especially the death of my grandmother, I realized how deeply denial affected my family. My mother, who was devastated by her mother’s death, found it difficult to accept the situation. Physiologically, this manifested as increased tension, sleep difficulties, and a visible refusal to acknowledge the vacuum created by my grandmother’s absence. Witnessing this within my family highlighted the complex and nuanced nature of the denial stage, not just on an individual level but also its ripple effects on familial dynamics.

Navigating the Anger Stage of Grief

The relentless wave of pain and rage starts to rise as the last remnants of denial slowly get out of control. People protect themselves from the unpleasant truth of loss when they are in the denial stage. However, as the protective veil of denial lifts, the rawness of the situation becomes apparent, birthing the second stage of grief: anger. From a biological perspective, the body’s reaction to grief changes as one moves from denial to anger. The physiological impact may have been momentarily suppressed by denial, but the emergence of anger reignites the stress response. Adrenaline rushes, cortisol levels rise, and the body prepares to fight against the perceived injustice.

Psychologically, anger surfaces as the mind grapples with the stark truth. The transition is like a fire that was previously dormant but now has regained strength after being deprived of oxygen. In my experience as a trainee therapist, I encountered a client moving from denial to anger after the loss of a loved one. After the client’s first shock subsided, a raging flood of emotions, a turbulent river of emotions looking for a way out, emerged.

Also Read: In the times of Death, Loss and Grief

A Therapist’s Insight into the Grief Labyrinthg:

It took professionalism, comprehension, and acceptance that, despite its intensity, anger was an essential phase in the grief process to go through this shift. It emphasized how the phases were related to one another, each easing into the next and assisting people in navigating the maze of grief. Indeed, at this critical juncture, grasping the complexity contained in the client’s rage is essential. As a counsellor, I saw that the client’s angry outbursts were a reflection of their inner conflict rather than a personal attack. The deep sense of powerlessness and lack of control over the overpowering waves of loss was the target of the intense and unwavering anger, not me.

Understanding that this anger was a response to the perceived injustice of the loss allowed me to approach the situation with empathy. It turned into a means for the client to express their feelings of unfairness and a moving way of expressing their internal turmoil. By acknowledging and supporting the client’s anger as a natural and valid reaction, we began a collaborative examination of the underlying emotions, setting the way for the next stage of the grieving process.

The third stage, bargaining, becomes evident as we make our way through the maze of loss; it is a moving interaction between hopelessness and desperation. The body may exhibit signs of fatigue, elevated stress levels, and abnormal sleep patterns from a physiological perspective. From a biological perspective, the stress response can cause variations in cortisol levels, which can affect general health. From a psychological perspective, bargaining becomes a fine dance between accepting that the loss is inevitable and wanting to make it go away.

A Dual Glimpse into Grief’s Emotional Landscape

Drawing from personal observations, I reflect on my mother’s journey through this stage when confronted with the loss of her own mother. It was an extremely emotional experience to witness her attempts to negotiate with the universe, to turn back time and change the unavoidable course of events. Navigating the bargaining stage with a client, as a counsellor, often involves providing a supportive presence and acknowledging their struggle to make sense of the irreparable loss. Offering empathy and understanding can create a safe space for the client to express their hopes, regrets, and attempts to negotiate with the pain.

This duality of on the one hand being a counsellor equipped with tools to help guide clients and on another hand with family members struggling with comforting them, highlights the unique challenges of identifying and grieving a loved one. It’s a poignant reminder that while professional expertise can be beneficial for clients, it doesn’t lessen the emotional weight of watching loved ones go through the complexities of loss.

The next stage, depression, manifests as both a somatic and an emotional dimension. Biologically, people can experience changes in appetite, sleep disturbances and lethargy. The physiological toll includes changes in neurotransmitters that contribute to frequent feelings of sadness. Psychologically, individuals experience a deep sense of loss, hopelessness, and constant melancholy, characterizing the emotional landscape.

Navigating the Depressive Phase

In my mother’s narrative, the depression stage unfolded as a symphony of sorrow. The previously vibrant social ties were overshadowed by a silent pallor that reflected the family’s collective grief. The biological rhythms of everyday life were disrupted and dark psychological voices echoed through the silent corridors of loss. Witnessing this process highlighted the complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social aspects of grief, shaping my understanding as both an observer and novice counsellor.

In fact, the depressive phase of the grieving process presents a unique challenge to both the bereaved person and those who support them. While earlier stages often involve more visible expressions of grief, such as denial, anger or bargaining, depression tends to develop internally and less publicly. The weight of their emotions may cause the person to withdraw, exhibit deep sadness, and undergo disruptions in sleep or appetite. Navigating the depressive phase with a client requires heightened sensitivity to nonverbal cues and greater awareness of subtle behavioural changes. As a counsellor, creating a sensitive dance involves creating a space that invites verbal expression while respecting the client’s need for solitude. Professional knowledge becomes crucial to distinguish between the natural progression of the stages of grief and the symptoms of clinical depression, which require further treatment.

Acceptance and Meaning in the Journey of Grief

In the final stages of grief, acceptance and the meaning of life, people often find a gradual reorientation to a new reality. Acceptance involves accepting the loss and integrating it into your life. At the same time, the search for meaning begins a search for purpose and meaning in the midst of pain. Some may experience these stages simultaneously, intertwining the process of accepting the reality of loss with the search for a meaningful existence beyond it. In my experience, this stage marks a turning point where people take action in their lives and embrace the changed reality with new purpose. It shows the flexibility and adaptability characteristic of the human spirit, reflecting the potential for change contained in grief.

Entering the culminating phase of grief—the search for acceptance and meaning—was an insightful exploration of my counselling training. I enriched my understanding through the theoretical background and personal observations, even though these stages were not directly developed with the client. Observing the complex dynamics of acceptance and the search for meaning in my own family, especially my mother, and through the grieving journey was deeply insightful. This highlights the complex interplay between accepting loss and finding a new purpose. This personal encounter reinforces the lesson that each individual and their bereavement experience is uniquely complex and emphasizes the need for tailored therapeutic approaches characterized by patience and empathy. As we anticipate these stages with future clients, this reflection underscores the importance of flexibility, openness, and an unwavering commitment to understanding the deep complexities of grief.

Leave feedback about this