“The poor kid cannot depend on his parents”, “her whole family is a bunch of thieves,” or “his bad genes made him like this.” These are some common phrases used for delinquent juveniles coming from unstable families. A person who had a privileged and affectionate childhood looks different from a person who lived in constant worry of being criticized, reprimanded or had to face severe emotional or sexual abuse.

What is responsible for a person’s criminal behaviour? Is it the bad genes or the poor environment? To answer this we must understand that all of us are born with a genetic foundation inherited from our parents. We grow up in environments with different stressors that trigger the expression of certain genes. This makes it essential to look at both aspects of criminal behaviour.

Criminal Behaviour

Criminal behaviour is detrimental to society, victims, family members of the criminal, and sometimes the perpetrator himself. It is loaded with emotional and material costs and destroys the sense of peace in a society. Such behaviour may be seen as non-adaptive or antisocial, generally defined as “behavior that violates the basic rights of others” (Calkins and Keane, 2009). To be antisocial is to be anti-society, against norms, rules, and regulations.

An antisocial person feels that societal rules and norms do not apply to him, often vandalizes property, risks life of his own and others, lies, steals, hurts animals, lacks empathy, and remorse, and deceives others for self-interest. Common motives behind these actions include the pursuit of gratification, teaching someone a lesson, and retribution. Looking at criminal behaviour from the vantage point of both nature and nurture allows various factors to come into focus.

Is it Nature?

Looking at the nature aspect is important because genetic predispositions could nudge people toward criminal behaviour. It includes biological factors such as brain structure, role of neurotransmitters, and genetic composition.

Genes:

Genetics play a role in various psychological disorders like depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. Researchers have worked to identify “criminal genes” that may be used as markers to identify people who are genetically predisposed to commit crimes and display extreme aggression. Studies have shown that monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) is responsible for the metabolism of neurotransmitters. It is associated with regulating aggression and its absence or low activity (MAOA-L) results in high impulsivity and lower self-control which makes people act in extremely violent and aggressive ways.

Brain structure:

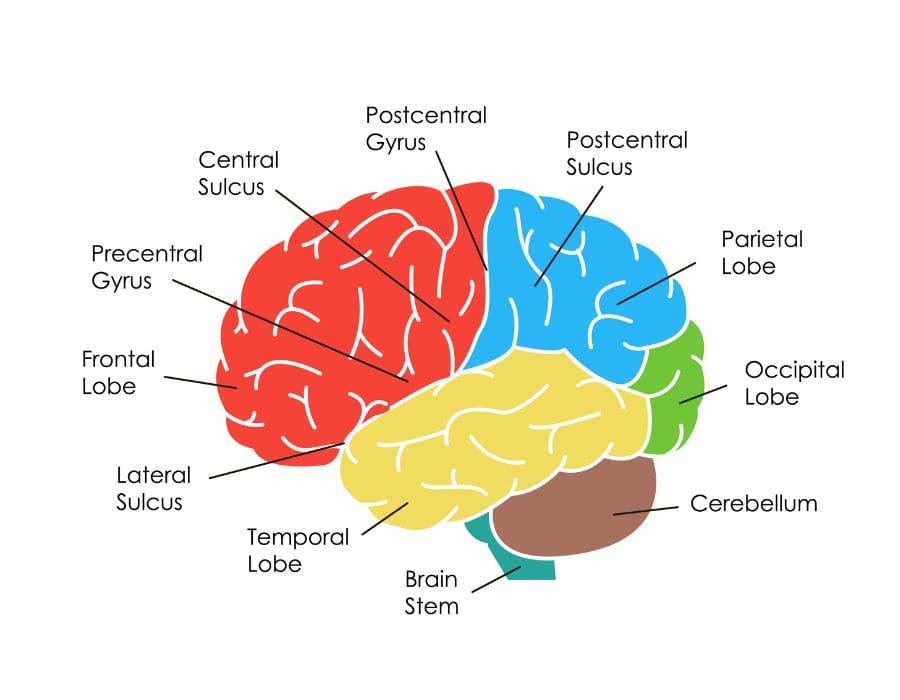

The cerebral cortex is divided into two hemispheres- right and left. Each hemisphere has four lobes. The frontal lobe has been given enormous importance while studying criminal behaviour because it is the seat of planning, executive functions, abstract thought, concentration, and inhibition.

Raine et al. (1997) found reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system of these offenders compared with control non-criminals. Brain imaging studies have found reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with ASPD. Additionally, Raine et al. (2000) found people with ASPD to have a decreased volume of grey matter.

Neurotransmitters:

Scientists have found that excessive levels of dopamine have been linked with aggressive and criminal behaviors. Reduced levels of serotonin are linked to criminal behaviour and the neurotransmitter manages impulsivity (Brizer, 1988; Raine, 2008).

Is it Nurture?

Social environments that foster a sense of belongingness, affiliation, trust, and safety help discourage criminal behaviour while those with exploitative, unpredictable, violent, and low support and affiliation patterns are breeding grounds for criminal behaviour. These environments convey different ideas about relationships, gratification, and social norms.

Relationships:

People who hold a hostile view of relationships are distrusting, and cynical, view people as different and unworthy of themselves, and lack empathy and regard for others. They are hypersensitive to disrespect and feel that others want to exploit them. This view of relationships is displayed by aggressive children and adolescents. (Burks et al., 1999; Dodge et al., 1990, 2002; Zelli et al., 1999). Emotionally distant and harsh parenting also makes it difficult for people to interact warmly with others. Exposure to racial discrimination and deviant peer groups also adds to it. Living in neighbourhoods with high rates of crime normalizes behaviours of deception, cruelty, and violence.

Gratification:

Self-control refers to inhibiting impulses and delaying gratification to avail rewards in suitable moments. It is at the centre when studying criminality. Exposure to such beliefs as the world is unjust, there is no future, and not being able to think of long-term benefits encourages impulsivity and risky behaviours. Individuals who face racial discrimination or live in environments where deception is acceptable are more likely to engage in an impulsive pursuit of rewards.

Social norms:

Viewing social rules and norms that prohibit promiscuity, lying, stealing, conning and substance abuse in a negative light increases the tendency to engage in criminal behaviour. Safe neighbourhoods and good parenting styles increase the likelihood of accepting social rules. However insensitive parenting styles, unpredictable environments, distrusting worldviews, and an inability to delay gratification for the better all contribute to acting against these social norms. This type of behaviour is commonly observed in people with an antisocial personality disorder.

Read More: Different Parenting Styles: How it Affects the Development of the Child

Integrating Nature-Nurture Perspectives

Genetic factors cannot defend against behaviours such as lying, manipulation, and exploitation. Research makes it evident that certain biological conditions significantly impact the ways an individual reacts and interacts with their environment (Rowe, 1996). It is necessary to see biological and social contexts are interrelated instead of separate aspects. This makes it necessary to take into account both factors while studying criminal behaviour. Social learning theory suggests that we learn behaviour through modelling, observation, and reinforcement. Our biology and genetics play key roles in defining rewards, pleasure, and pain.

The connection between biology, social learning, and criminality is well illustrated in Gottfredson and Hirshi’s (1990) notion that self-control largely predicts criminality, although parental practices are primarily responsible for developing the child’s level of self-control. To say that either self-control or parenting matters the most is wrong. Parenting serves as the mediator between self-control and criminality. Although, social learning can largely predict criminal behaviour, growing research indicates that biology plays a considerable role in what and how we learn.

Relying too heavily on just one approach to understand criminal behaviour would be futile and inaccurate. Numerous studies highlight the importance of understanding the interplay between both factors. Therefore taking both biological factors and social understanding of criminal behavior can advance our knowledge of criminal behavior. This integration would lead to increased scope, validity, and accuracy of the theories describing criminal behaviour.

Conclusion

It is essential to research criminal behaviour and the questions it poses. The present literature emphasizes the role of biological factors like brain structure, neurochemistry, and genes and social factors like parenting, view of relationships, discrimination, and attitude regarding social conventions. Looking at the dynamic interplay between nature and nurture will help take preventive measures, rehabilitation, designing strategies, and counselling. As parenting styles play a crucial role in the development of such behaviour, better information about child rearing will be effective. Safe neighbourhoods with the provision of basic amenities might also help in curbing crime rates. Early screening of at-risk children will help in designing interventions timely.

Overall, it can be concluded that none of the factors should be overlooked when understanding criminal behaviour. Overlooking any of the factors would lead to ineffective measures and strategies.

FAQs

1. What is Antisocial Personality Disorder?

Ans: the presence of a chronic and pervasive disposition to disregard and violate the rights of others. Manifestations include repeated violations of the law, exploitation of others, deceitfulness, impulsivity, aggressiveness, reckless disregard for the safety of self and others, and irresponsibility, accompanied by lack of guilt, remorse, and empathy.

2. What is social learning theory?

Ans: the general view that learning is largely or wholly due to modelling, imitation, and other social interactions. More specifically, behaviour is assumed to be developed and regulated by external stimulus events, such as the influence of other individuals, and by external reinforcement, such as praise, blame, and reward.

References +

Boller, A. L. (2021). Criminals: Made or Born. Twentyfirst Edition. RAMS Radboud Annals of Medical Students, 16-17.

Taylor, S., PhD. (2020, November 30). Perhaps they are natural born potential killers. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/you-me psychology/202011/are-serial-killers-born-or-made?msockid=2f85ff6bde056ff70bd2ee59dff86ed3

Nickerson, C. (2023, September 29). Biological theories of crime. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/biological-theories-crime.html#History-and-Overview

Baskin, J. H., MD. (2019, January 13). Exploring factors contributing to criminal behavior. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/cell-block/201901/what makes-criminal

Fox, B. (2017). It’s nature and nurture: Integrating biology and genetics into the social learning theory of criminal behavior. Journal of Criminal Justice, 49, 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2017.01.003

Simons, R. L., & Burt, C. H. (2011). LEARNING TO BE BAD: ADVERSE SOCIAL CONDITIONS, SOCIAL SCHEMAS, AND CRIME*. Criminology, 49(2), 553–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2011.00231.x

APA Dictionary of Psychology. (n.d.). https://dictionary.apa.org/