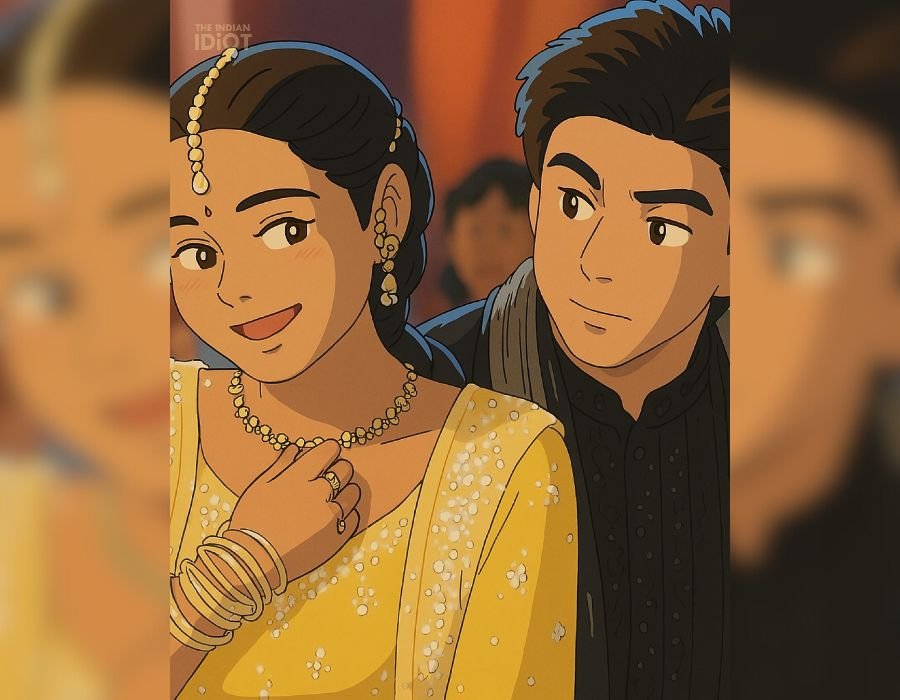

You scroll through your feed and pause. You see someone you know, but not quite. Their face is softer, their eyes wider, the background dreamier. They’ve been turned into a Ghibli character. So has your classmate. Your cousin. Your favourite creator. Suddenly, the internet feels like it’s living inside a Studio Ghibli film.

It’s easy to see why this trend is so loved. It’s fun to try, beautiful to look at, and easy to share online. But alongside the excitement, discomfort has started to surface. Artists, fans, and everyday users are expressing concern. Some feel that using AI to imitate Ghibli’s iconic style disrespects the human craft behind it. Others feel protective of Ghibli’s legacy, or even frustrated by how easily doing art can be automated. Some also have broader concerns about the erasure of artistic labour and creative theft as well as the environmental cost of AI.

These mixed reactions reflect deeper psychological dynamics around identity, beauty, belonging, and ethics.

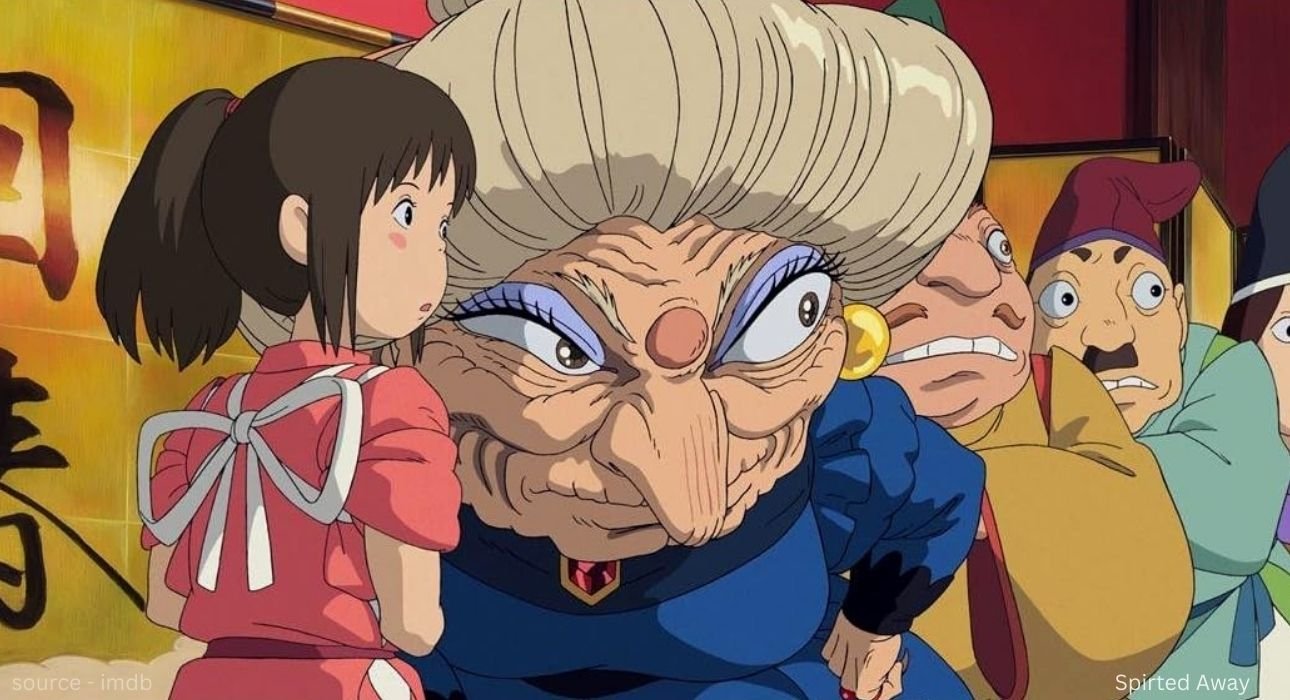

Why Ghibli Art Moves Us All

The Ghibli aesthetic is instantly recognisable with its expressive faces and serene, everyday sceneries. These beautiful visuals stir up emotions within us. Aesthetic psychology tells us that we’re drawn to art that resonates emotionally, especially visuals that feel warm, safe, or familiar (Silvia, 2005). And the Ghibli aesthetic checks all those boxes. These elements create “affective responses”. These are feelings that arise automatically when we encounter emotionally charged stimuli (Leder et al., 2004).

From a neuroaesthetic perspective, the soft lighting, human-like characters, and immersive nature settings activate the brain’s reward systems. This results in the release of dopamine and promotes a sense of comfort and joy(Chatterjee & Vartanian, 2014). So, these happen to be deeply felt experiences rather than passive reactions.

This emotional connection is also tied to nostalgic escapism, which is our tendency to seek comfort in idealised memories or familiar aesthetics, especially during times of uncertainty. Even when people know the images are AI-generated, the emotional cues they associate with Ghibli’s art don’t just disappear. The feelings of “magic,” “peace,” or “childlike wonder” still show up. This helps explain why this trend started.

According to Clinical Psychologist Gavneet Kaur Pruthi, The text discusses the trend of people being drawn to cosy and safe feelings, possibly triggered by technological advancements and social media. It notes the rise of Al tools capable of generating Ghibli-style images, making it easier for people to visualize themselves within this aesthetic. The conclusion suggests that the obsession with the Ghibli art style is rooted in psychology, citing nostalgia, escapism, aesthetic appeal, and social trends as contributing factors. People desire Ghibli-style images for various reasons, including childhood memories, magical escape, or simply artistic style, and the appeal of Ghibli-inspired portraits is unlikely to fade anytime soon.

Why People Participate in this Trend

So, why are so many people enthusiastically transforming themselves into Ghibli-style characters and sharing them online?

At a surface level, the appeal lies in how easy and beautiful the results are. With just a few taps, anyone can produce a Ghibli-style image of oneself without any artistic skills. At a deeper level, there are several psychological phenomena at play.

From a social psychology perspective, one key factor is the concept of social proof. Social proof is the idea that if everyone around us is doing something, it must be worth trying (Cialdini, 2007). As users scroll through their feeds, seeing friend after friend post Ghibli-style images, it creates a subtle pressure to join in. So participation becomes not just an option, but a social norm.

Closely related is the desire for ingroup belonging. Posting an AI-generated Ghibli image becomes a form of shared ritual. In a fast-paced, fragmented digital world, these moments of shared aesthetic experience allow people to feel part of something collective. According to the Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), such behaviours help reinforce group membership and social identity.

The trend also ties into the idea of positive self-presentation. Online spaces often serve as curated extensions of the self. What we post online allows us to express our traits. In the case of the Ghibli-style image trend, we have the opportunity to express traits like creativity and an eye for beauty.

From a cyberpsychology lens, the trend reflects how digital tools enable low-risk self-expression (Suler, 2004). AI offers a playful sense of creative agency without the vulnerability of traditional artistic effort. So, the Ghibli-style images feel like a safe form of experimentation, where users can imagine alternate selves as possible Ghibli characters.

This is related to the concept of possible selves (Markus & Nurius, 1986), or the imagined versions of who we could be. In the Ghibli aesthetic, users may see not just their faces but their idealised inner worlds. And sharing these versions online becomes a way to invite others into those worlds.

For many, the trend is lighthearted and empowering. But not everyone feels this way. As we move to the next section, we explore the psychology of another group of people who are wary and critical of this trend.

Understanding the Dissent

Critics raise valid concerns: the loss of artistic labour, ethical boundaries, copyright infringement, and environmental impact of AI models. But beneath these concerns lies something deeper and more psychological.

According to the Moral Foundations Theory (Haidt, 2012), our moral judgments come from five innate, intuitive foundations. These are (1) care/harm, (2) fairness/cheating, (3) loyalty/betrayal, (4) authority/subversion, and (5) sanctity/degradation. When it comes to the AI-Ghibli trend, those intuitions are being stirred. For many who feel uneasy about this trend, it’s about fairness (care/harm), a sense that true art requires human intention and effort (authenticity), and a feeling that something sacred is being diluted when handcrafted beauty is replaced by algorithmic replication (sanctity). These reactions aren’t merely an opposition to AI art. They’re emotionally charged responses rooted in what people sense is being threatened.

For individuals who see art as a profoundly human craft, seeing it mimicked by a machine can trigger cognitive dissonance (Festinger, 1957). There’s a psychological tension when the cultural response to AI-generated art seems to contradict one’s belief in creativity as a deeply personal activity that requires time and effort. This discomfort then evolves into a shared sense of loss. Human art represents values like creativity, dedication, care, and originality. When it feels like these are being lost, it leads to collective grief.

This sense of loss can further lead to existential anxiety. This is especially true when it feels like human imagination is being converted into algorithms. As Gunkel (2022) notes, anxieties around AI often stem from the blurred line between human uniqueness and machine imitation. The fear is about whether creativity, something long considered uniquely human, is now up for replication.

From a psychological perspective, expressing dissent towards AI art is a form of identity-protective cognition (Kahan, 2012). This refers to the emotional rejection when new trends threaten core beliefs about self, society, or the sacred.

Conclusion

The Ghibli-style AI trend provides us with a glimpse into how we respond to evolving technologies. Despite the differences, both reactions come from the same place: a deeply human instinct to create and to preserve what we hold dear. As we keep crossing paths with new tools that blur the line between human and machine, the question we’ll keep facing is this: how do we embrace what’s new without losing what we value?

FAQs

1. Why are people so emotionally affected by seeing themselves in Ghibli-style images?

These visuals evoke a romanticized version of life where everything is calmer and more whimsical. Seeing yourself in that world evokes deep emotional longings for simplicity, safety, and beauty.

2. How does nostalgia play a role in the trend’s popularity?

Ghibli’s art style is loaded with emotional memories from movies in our childhood and even collective cultural symbols. The trend uses nostalgia to make the images feel comforting and ideal.

3. What does the trend reveal about our mental health and emotional needs?

The trend might be an indication of how emotionally adrift or overstimulated people feel in real life. The desire to “escape” into art could reveal unmet needs, like rest, meaning, gentleness, or emotional visibility.

References +

- Chatterjee, A., & Vartanian, O. (2014). Neuroaesthetics. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(7), 370–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.03.003

- Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Influence: The psychology of persuasion (Rev. ed.). Harper Business.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

- Gunkel, D. J. (2022). Person, thing, robot: A moral and legal ontology for the 21st century and beyond. MIT Press.

- Kahan, D. M. (2012). Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection. Judgment and Decision Making, 8(4), 407–424. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2182588

- LaFollette, H., & Woodruff, M. L. (2013). The Righteous mind: Why good people are divided by politics and religion. Philosophical Psychology, 28(3), 452–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2013.838752

- Leder, H., Belke, B., Oeberst, A., & Augustin, D. (2004). A model of aesthetic appreciation and aesthetic judgments. British Journal of Psychology, 95(4), 489–508. https://doi.org/10.1348/0007126042369811

- Markus, H., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41(9), 954–969. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.9.954

- Silvia, P. J. (2005). Emotional responses to art: From collation and arousal to cognition and emotion. Review of General Psychology, 9(4), 342–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.4.342

- Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 7(3), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1089/1094931041291295

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

Leave feedback about this